Here we go, falling in love with writing again.

Non-Conformity

For nonconformity to exist we’re saying that there’s conformity, a uniform, a code that’s in place. By wilfully not conforming we’ve eschewed protocol, jumped a red light, and ignored convention. We might well create our own protocols, put a new traffic system in place and hold a convention for other like-minded rebels to celebrate the new (non)conformity. This is often what we call progress.

Rebellion on masse accentuates conformity, gives the status-quo definition and clarity. Rebellion is the mental and often physical manifestation of the alienation that we feel. But this book isn’t necessarily about us on masse, we’re looking at us as individuals.

When we talk about creativity and nonconformity, in the context of this book, we’re talking about auteurs, accidental anarchists and those that refuse both to be boring and to be bored by others. This is about the eccentricity that pulses through our veins.

Paradoxically, the fact that we feel isolated and dislocated in some way from society is what unites us. We can move on. Nonconformity isn’t limited to political or cultural agitators. Nonconformity can be nuanced: A flourish or a finesse. Eccentricity is arguably, an exaggerated performance of ‘normal’. Normality is a dulled and muted perception of life. Normality borders on the non-existent, eccentricity surrounds us.

Let’s not confuse this refusal of normal with an entire rebuttal of shared values and ethics, of education and learning, of standards in skills and democratic agreement on elements of life that prevent us from harming others. We could argue a case for that, but, again, this isn’t the place for such. Creating a framework, boundaries and limits are liberating: Rebellion is also a considered system.

Back to eccentricity. What has nonconformity ever done for creativity? If we swap the question round we can see that creativity, a tool of expression, is instrumental in voicing the nonconformist self.

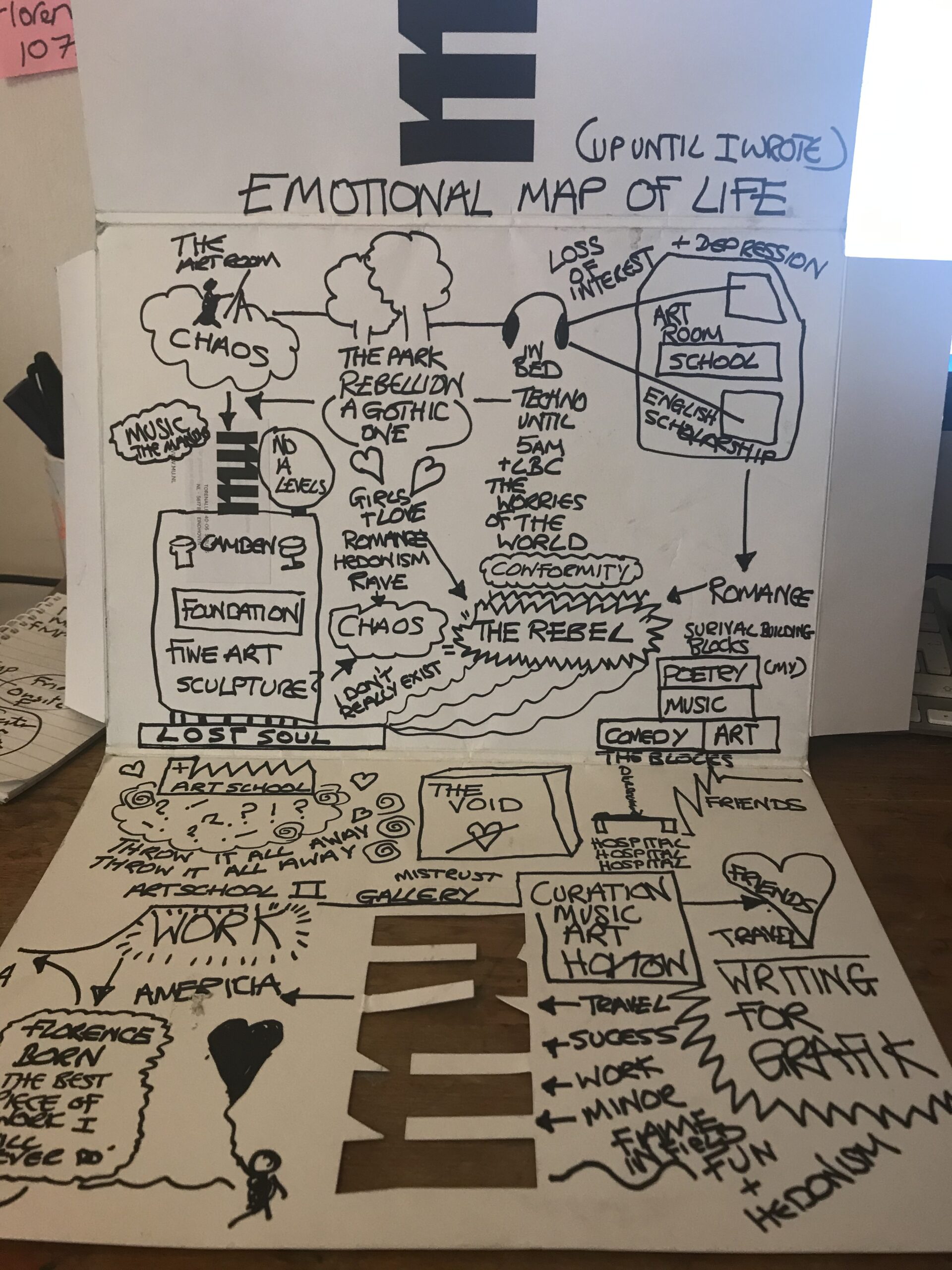

The pandemic altered the shape of my career. Prior to March 2020 I was teaching and writing sporadically, as an editor at large for Elephant magazine I was chugging along, a piece in every issue for the past five years, a career of about 15 years, first as a staff writer for Grafik, then as a freelancer, writing for almost every design and arts publication out there. I’d fallen into writing about design accidentally. Nepotism had got me my position at Grafik. A good friend of mine, Angharad Lewis had become editor there in 2005 and, as I was known amongst friends for my poetry, she asked me to review an exhibition. Soon I was part of the small, but well-formed team, at the tail end of an era in publishing where there was an office, in Portland Street, a budget to travel, and respect from the design community that opened doors. I never quite feel imposter syndrome but I did feel slightly askew to the world that I was to cover. I wasn’t trained in design, but fine art, I wasn’t a fanboy or girl. My interest was in the human angle to creativity, and it might have been because of this that I became sought after – whilst others waxed lyrically about the latest tool or technique I was more interested in the back story, the whys.

René Knip: In Between Language and Landscape (taken from Grafik magazine article I wrote)

‘René Knip is in full flow talking about his collection of visual resources “I follow a lot of subjects, I follow trees, plants that survive when they grow in and between buildings, sleeping white animals, I follow stairs, just two or three-step stairs, I follow old barns, the little barns where people do not live, I follow shadows, the black drawings of shadow lines…”. I’m in a car with René driving through the Dutch countryside, we’re following the road that takes us past his restored farmhouse studio on our way to lunch in Harlingen, a seaside town not far from the small town of Sneek, about 2 hours northwest of Amsterdam by train. “No, I don’t have a lot of heroes” he continues, “I’m influenced by everything I see, by walking, by architecture I guess…” Distracted by an old man sitting by the side of the road René gestures over approvingly, “look at that, disappearing life, just an old man living on a farm, just sits there all day, if a tile falls off the roof he puts another one on…”